On October 20, I had the wonderful opportunity and priviledge to present the following paper at the 2018 UC Berkeley Comparative Literature Conference Future (Im)Perfect. This paper is a super rough draft of a paper that I am developing, but enough people have expressed interest that I thought I would share it now.

On the Possibility of Plant Knowledges

Michael Song, PhD Candidate

The tree will have a consciousness, then, similar to our own? Of that I no experience. – Martin Buber (1958).

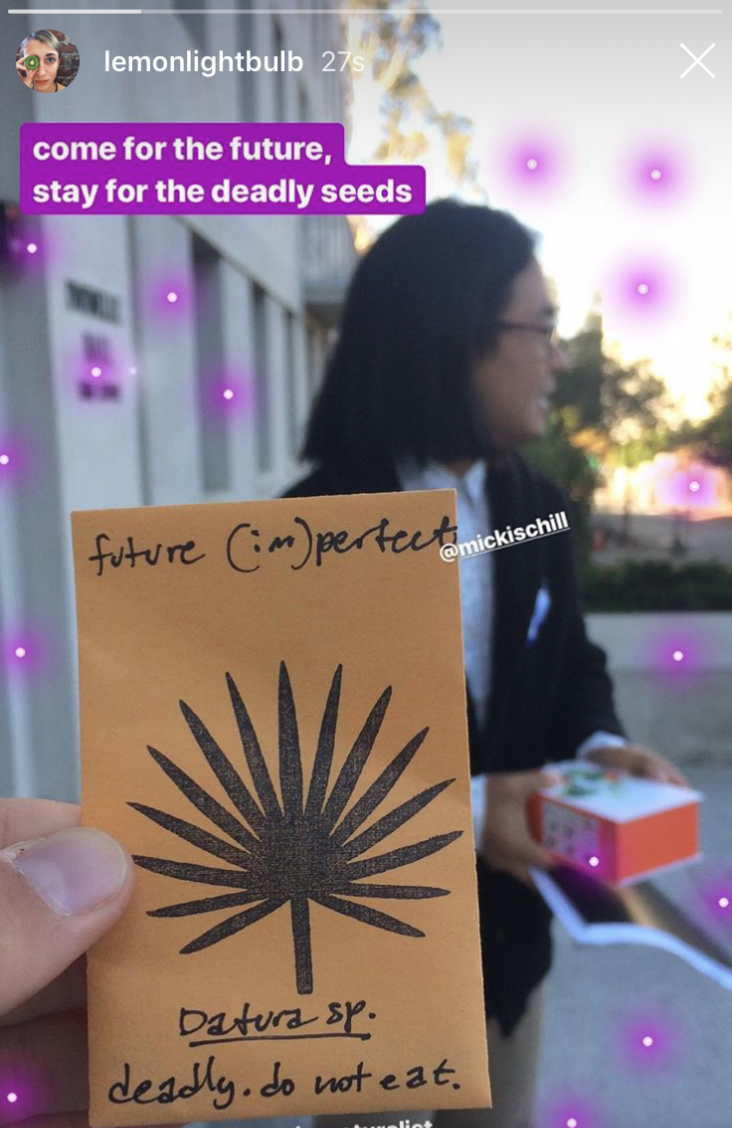

[Here we find ourselves in Ishi Court, a garden. Before I give my talk, I offer a gift to the participants. In these envelops are the seeds of a plant with many names. It is known as Datura from the Sanskrit dhattura meaning “white thorn-apple,” or moon flower since it blooms at night. Devil’s trumpet and hell’s bells, Devil’s cucumber. The Tongva call it manit and the Chumash momoy. It is known as tolguacha in Mexico and botanists know it as Datura wrightii. These seeds are for you to take and plant. These seeds are extremely poisonous, they are deadly, but they are also used medicinally and spiritually and are the source of many knowledges.]

In the two creation stories of Genesis, the garden precedes the creation of man. The trees and rivers are known to God as trees and rivers—already with names. But when man is created, “God formed every animal of the field and every bird of the air and brought them to the man to see what he would call them; and whatever the man called every living creature, that was its name” (Genesis 1-2). Put differently, man does not name the plants. Such knowledge exists outside of the scope of man, and in fact, plants give language to humans via “the tree of the knowledge of good-and-evil” [a merism meaning “everything”]. This unnameability of plants implies that there are knowledges that exist outside of the human.

Naming and discerning difference is how man distinguishes humans as apart from animals and is the foundation of humanist knowledge. In their discussion on “Becoming-Animal,” Deleuze and Guattari talk about the different appraisals of animals such as “species, general forms and functions” noting how “Society and the State need animal characteristics to use for classifying people; natural history and science need [animal] characteristics in order to classify the animals themselves.” Yet, we lack a plant language to name plants themselves. When we describe plants, we are really describing animals. Think about the ovaries of a flower, the androecium or gynoecium, or how even the metaphor of the rhizome with its “short-term memory,’ “circulation of states,” and “directions in motion,” has animal characteristic namely memory, movement, and circulation. This language which divides man and animal remains central to the Humanities, where what it means to be human is defined through the dialectics of self and other. Humanism grants to humans the ability to create difference by “attributing to man a power that animals lack… [such as] the ability to dress, to bury, to mourn, to invent, to control fire… often that women, children, slaves, foreigners, and others also lack” (Elizabeth Grosz 2011). But if we return to the creation story in Genesis, we may wonder what the plant knowledge of everything was that the Tree of Good-Evil gave. We named the birds and the beasts before consuming plant knowledge, and we arguably still operate under this pre-tree animal-naming framework of knowledge. But if plant knowledge exists outside of this, what is it and how do we access it?

Instead of focusing on how plants appear to engage with concerns that are often confined to human activity such as ethics and aesthetics, a line familiar to those of us who think about animal subjects, I want us to move away from a humanistic perspective and think about traits in terms of how they are shared and accessible qualities of the taxonomic group of all living things. The trait in question is plant knowledge. I am preoccupied with how the humanities and the sciences both have often independently attempted to arrive at a plant knowledge, the problems faced by such attempts, and the potential that the transformation of subjectivity necessitated by these attempts can have for a future system of ethical values. What is at stake in these and future attempts at plant knowledge, a knowledge that is outside of and encompasses more than the human, is the future of knowledge after we go existent as species—a future imaginary that scientists and humanists are converging upon in the face of the tragic, ongoing, and worsening consequences of global warming and climate change.

Perhaps plant knowledge can be accessed through metaphorical language which escapes the problem of naming. Hans Blumenberg, in Paradigms for a Metaphorology (1960), defines a discipline which “aims to show with what ‘courage’ the mind preempts itself in images, and how its history is projected in the courage of its conjectures” (5, trans. Robert Savage). In examining metaphors, Blumenburg is careful not to not only outline a scheme where metaphors transform into concepts, but where concepts can also transform into metaphors as well. He describes how metaphors are used as placeholders when we do not have a concept of how things work, but also shows how when we have a concept of how things work, these concepts can be transformed into metaphors through their reception, such as the reception of the ideas of Copernican reforms “not as an item of knowledge, nor as a hypothesis, but as a metaphor!” (101). In this same way, Darwin’s concept of the common descent of all living beings and the evolution from common ancestors by means of natural selection was received as the metaphor of the tree-of-life. By challenging the metaphor of the scala naturae (the Great-chain of Being from Antiquity, which establishes hierarchical relationships from the most basic of things (rocks, then plants) to the most highest perfection (god at the top followed by angels, man, and then animals), the Tree-of-life metaphor is a projection that gave “structure to the to the world, representing the non-experienceable, non-apprehensible totality of the real” (14), where interpretations may still be difficult but where nonetheless man is displaced from his previous position in the hierarchy of living being. The tree is here a metaphor, but trees are also living beings, our relatives, that exist outside of metaphors. That Darwin and his followers would co-opt the tree for their newly imagined metaphor of the tree-of-life demonstrates our complicated relationship to plants and the production of non-human knowledges.

Charles Darwin (1809-1882) was primarily a geologist and botanist and whose plant collections of the unique flora of the Galápagos preceded Finches in inspiring his evolutionary thought. The metaphor of the tree-of-life gives the courage to imagine a de-anthropomorphized human species: Man no longer as the measure of all things as he is in the tradition of classical humanism. Freud describes this as a blow to the universal narcissism of man: “not being different from animals or superior to them; he himself is of animal descent, being more closely related to some species and more distantly to others” (‘A Difficulty in the Path of Psychoanalysis’, 1917). In Darwin’s words, “the difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, certainly is one of degree and not of kind,” demonstrating that all difference from the most diverged lineages of fungi, bacteria, plants, and animals are ones of “degree” and not of “kind” (The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, 1871) Naming is the process by which we distinguish different kinds of things, but measuring is how we discern the degree of difference between things of the same kind. In this way, the universalizing quality of the tree metaphor offers the potential to learn about life outside of the practice of naming. This taxonomic innovation of Darwin completely reimagined what traits are, by attributing the qualities formerly attributed to only one “kind” (usually man) all throughout the tree-of-life, such as the trait of intelligence being now understood as evolving from a common ancestor. Knowledge becomes then a property of life and the metaphor of the Tree-of-life shows the courage of the mind to think ahead of itself and stands in for a “objectively unobtainable whole” (17) conception of life where the hierarchies are now genealogical and the traits of life no longer need be anthropomorphic.

The totality and oneness of the plant also lends itself for use as a knowledge metaphor, and has an interesting precedence in Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832), whose treatise Versuch die Metamorphose der Pflanzen zu erklären (Metamorphosis of Plants, 1790) introduced the idea of transformational homology in development which is now the organizing principle of the burgeoning field of evolutionary development (Evo-Devo) in the biological sciences. Goethe hypothesized that “the plant is nothing but leaf, which is so inseparable from the future germ that one cannot think of one without the other.” Goethe is saying quite literally that plants are comprised of transformed leaves, but keeps open the possibility that all life may be metaphorically a leaf, serially homologous parts of the whole tree of life. In the proem to the book he writes, “the plant-child, like unto the human kind—/Sends forth its rising shoot that gathers limb /To limb, itself repeating, recreating,/In infinite variety” (3). For Goethe, we are ruled by the same laws of the ideal and knowledge of the ideal laws has the power to transform us when we see the similarity, homology, between different things. In this poem, we find the flowers themselves declaiming the eternal laws, knowledge that they not only communicate to us via our deciphering them, but that they embody biologically. But how is it possible to understand flower-subjectivity?

Is there any potential for plant intersubjectivity? Martin Buber (1878-1965), in his Ich und Du (I and Thou), describes a scientific approach to considering a tree, “I can classify it in a species and study it as a type in its structure and mode of life. I can subdue its actual presence and form so sternly that I recognize it only as an expression of law.” Buber here illustrates for us the limitations that the scientific methods have in approaching plant knowledge as being akin to Goethe’s idealism, but without Goethe’s aspiration towards knowledge of the ideal: the laws are already known. The philosopher Rosi Braidotti (b. 1954) tells us of the dreary current state of affairs, “Science and technology studies tend to dismiss the implications of their positions for a revised vision of the subject. Subjectivity is out of the picture and, with it, a sustained political analysis of the posthuman condition” (The Posthuman, 2013). By ignoring the subjectivity of science, scientists close themselves off to displacing themselves from their center position in knowledge generation, denying themselves the courage of the metaphors to foretell the truth, and denying the possibility for plant knowledge. Buber offers the possibility however, “that in considering the tree I become bound up in relation to it. The tree is now no longer It… The tree is no impression, no play of my imagination, no value depending on my mood; but it is bodied over against me and has to do with me, as I with it.” This experience of the tree itself is still marked by a relationship in which man may become whole in his experience with another being, but the traditional humanistic unity of the subject remains unbroken.

Is, however, the reverse of this I-Thou relationship plant knowledge? As I encounter the tree in a I-Thou relationship, the tree encounters me. What does a tree encounter of me (the object of the subject tree’s encounter), feel like? Perhaps we can approach this question through the lens that ethnobotanist Gary Paul Nabhan (b. 1952) employs when he writes that for the Papago Indians “a saguaro cactus is ‘that which is human and habitually stands on earth’… it strikes me that the Papago liken saguaros, Cereus giganteus to Homo sapiens because no matter how much they tend to dominate the landscape, they are still vulnerable” (Nabhan 1982, 26). It might seem that here humans are the metaphor for the saguaro cactus. But saguaros are humans for the Papago (26), they are classified as a part of humankind, and so this is not metaphorical language: it is knowledge of life that derives from life, not human nor plant, but is plant knowledge—all life nested in the great family of plant-animals. Here we find neither metaphor nor concept, but a glimpse of life knowledge through a subjectivity that includes non-human agents. Braidotti explains the consequences of such a transversal entity as “firstly, it implies that subjectivity is not the exclusive prerogative of anthropos; secondly, that it is not linked to transcendental reason; thirdly, that it is bases on the immanence of relations” (The Posthuman, 82). Though they are living neither in the Darwin’s humanistic interpretations of the tree-of-life metaphor, nor the Goethean metaphor of the leaves of the tree-of knowledge and its transcendental laws, are the ways that the Papago embody plant knowledge really that dissimilar to Buber’s Ich-Du encounters? Still, there is a distancing and differentiation of the subject. For Buber, distance (Urdistanz) is a precondition for there to even be relations (Beziehung) and so humans even as they may exist as trees remain special as the only beings who truly distance, and remain the only subjects that have a “world.” How can we then reconcile distance and difference with the possibility that all life or all matter may be wishing to form and express themselves in the world?

We may look to science once more, in whose concepts we find courageous metaphors! Currently new statistical methods in the field of evolutionary biology has allowed us to infer phylogenies (the evolutionary relationships) of the entire tree-of-life in a probabilistic framework that can include the placement of the millions of fossils that we have collected from the geological record. For the first time we are able to incorporate both living taxa and extinct taxa and many scientists are occupied with mapping what they are calling the Tree-of-Death. In the final part of this paper, I want to explore the ethical potential of this metaphor as an approach to grasp once more at a plant knowledge.

The Tree-of-Death as metaphor is different from the last two tree metaphors we encountered the Tree-of-Life and the Tree-of-Knowledge. The Tree-of-Life is a way of understanding the entirety of life as being like a tree, differentiating branches that though are of one “kind” and started from one seed nevertheless grow with different trajectories. The Tree-of-Knowledge is a way of understanding the entirety of knowledge as being like a tree, modular and transformational expressions of universal laws embodied in every branch, leaf, and flower, so that life is seen as a sequential transformation of these laws. But the Tree-of-Death as a metaphor is a way of understanding the entirety of life as being like a tree whose differentiation between branches is the negative space of death. Death prunes the branches and separates them from each other and is only tree-like because of the creative power of death. What then relates life, is no longer differences of degree or transformations of expression, but the very qualities of life the fact that we are all living. In a way, this quality of life abolishes the directionality of the tree, the hierarchy of organization and the degrees of difference and returns this tree to its mere plant-ness, what Deleuze and Guattari foretell as “a tree branch or root division may begin to burgeon into a rhizome” (15). The Tree-of-Death is the Plant-of-Life and calls us to a new plant knowledge.

Plant knowledge must exist in as aspiration then, through brave metaphors that precede it, its potential always lying in the future. The continual attempt at plant knowledge is a serious endeavor. In particular, the aspiration towards an understanding of plant knowledge will inoculate against a major ethical problem posed by Braidotti. She criticizes the movement towards a “trans-species embrace [which] is based on the awareness of the impending catastrophe… [and] promotes full-scale humanization of the environment.” This embrace maintains the dualism between humans and animals, nature and culture, but allows for the bonding of living beings that suffer together and attempts to give liberal rights to all beings that suffer. This unimaginative reification of the human and his rights has not lead to any substantial mitigation of climate change or the sufferings it wishes to cure. What is being called the sixth mass extinction is actually occurring during a trend since the Cambrian Period (541 MYA) of steadily increasing diversity of living beings on Earth, with an even larger trend of increasing diversity since the Cretaceous Period (66 MYA). Under a Liberal framework, the human causes and human consequences of climate change prevent us from disentangling this idea of turnover of lineages (the death of some lineages and the creation of new lineages via splitting) with that of extinction of lineages (like Homo sapiens, which is what people are preoccupied about), because a Liberal framework operates to conserve the status quo, essentially imaging a fixed world, where things can be hurt, but nothing new can be created. The alternative to mitigating harm is the production of infrastructure to heal, and there is a role for the critical theorist and the scientist to provide new theories to challenge a model of simply harm reduction. The plant metaphors we explored today give us a sense that life is dynamic, related, connected, and non-hierarchical, that life is like the universe ever expanding outward without direction, and also gives us a sense that life is not just the state of not having died yet. Plant-knowledge as the foundation for a system of ethics, calls us to task to be as courageous as our metaphors are in preempting better versions of ourselves, which in a posthuman world includes the entire clade of life.