ἐπάμεροι: τί δέ τις; τί δ᾽ οὔ τις; σκιᾶς ὄναρ ἄνθρωπος. ἀλλ᾽ ὅταν αἴγλα διόσδοτος ἔλθῃ, λαμπρὸν φέγγος ἔπεστιν ἀνδρῶν καὶ μείλιχος αἰών -Pindar

Addendum

Over last year since writing this piece, Hum 110 reform has been actively fought for by students at Reed and the syllabus is being reviewed one year early. What the nature of the revised syllabus will be is still up in the air. However, I think that it is very important for an institution such as Reed to listen to its students of color and the demands they have. To tout the benefits of a “liberal arts” education without being critical of how pedagogy can perpetuate systems of oppression is hypocrisy for a college that advertises diversity. Only by listening to the students can educators learn how these texts can be used effectively.

February 14, 2017

History of Hum 110

Here at Reed College, Humanities 110 is on the lips of every man and in the heart of every child, or so they say [1]. There has recently (perhaps always) been controversy about the syllabus and these certainly are important conversations to have. I wish in this web-essay to first give a brief chronological history of Hum 110 to provide context for future discussions and then to look at the trends one may find by digging through past syllabi, asking questions along the way. I have digitized all of the Hum 110 syllabi in a spreadsheet that can be accessed upon request from Special Collections.

It was under Reed College’s second president, Richard F. Scholz (1921-24), that our familiar system of requirements arose and his pedagogical philosophy (which developed in response to the “elective-system” implemented under President Foster (1912-1921)) warrants note, “The course of study for the first two years covers the general field of the evolution of man in nature and society. It aims to lay the foundation of a well-rounded liberal education and to provide for the orientation which will assist the student to an intelligent and wise choice of a major interest to be pursued intensively during the last two years of the college course” [2].

![From Arragon, 1945 [Reed College Special Collections]](https://someessayslettersandcomplaints.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/screen-shot-2016-06-30-at-6-56-20-pm.png?w=1336)

According to Professor Arragon (1923-62), “The Scholz program, which remained basically the same until 1927, had as its central core, required of all but one group of students’, a two-year course in the history of civilization, paralleled by a two year course in world literature, both unusually well conceived in content and method, year courses in general biology and mathematical analysis, and the choice in the sophomore year of one of the broad introductory courses offered in economics, political science, and sociology” [2]. The sophomore requirement was later abandoned and in 1943 the freshman core in history and literature fused to form Humanities 11. Modern Humanities (now Hum 220) was offered beginning in 1947. As one of the architects of this merger, Arragon explains the philosophy behind the original iteration of the course, “It is historical in the organization of materials; but it is not primarily a chronological survey, for certain periods are singled out for emphasis. These are explored to the end of acquainting students with the development of western society and with its heritage of ideas and attitudes and of institutions and works of art, and of furthering their understanding of men and of society through the examination of particular human situations, actions, and expressions of the past” [2]. This emphasis on both literature and history is evinced by the dual model of teaching in conference, where conferences were conducted by a history and a literature professor. However, starting in 1949, conferences were lead by one professor in a manner more-or-less unchanged to this day (See Arragon, 1941).

The first major changes to the 1943 curriculum came in 1962 where the course was reduced from seven to six units and conferences were reduced in frequency to only three times a week. An historical narrative remained the driving force behind the syllabus, as History Professor Richard H. Jones (1941-1986) wrote in the Quest, “Despite much conscientious disagreement we have, however, developed much attention to the culture of Athens in the fifth and early fourth centuries, BC. Rome will be introduced only for the purpose of examining the problem of transition from republic to empire. The origins of Christianity will be studied. And the rest of the year will be devoted to early modern civilization as it was manifested in Western Europe: Italy, Germany, France and England with some reference to Spain and to the Low Countries” [3]. The Middle Ages were dropped from the curriculum entirely. Large changes to the syllabus continued throughout the Sixties and Seventies — a trend that former PR director Harriet Watson attributes to trends in higher education toward faculty specialization — reaching a boiling-point from 1973-79. During this period, the Humanities course was divided into a unified first semester focusing on Ancient Greece, followed by a spring semester where a student could choose from one of three offerings: A continuation of Ancient Greece (Hum 120, which lasted one year and was replaced by “the Middle Ages and Renaissance”), the Italian Renaissance (Hum 130), and late medieval and early modern England (Hum 140).

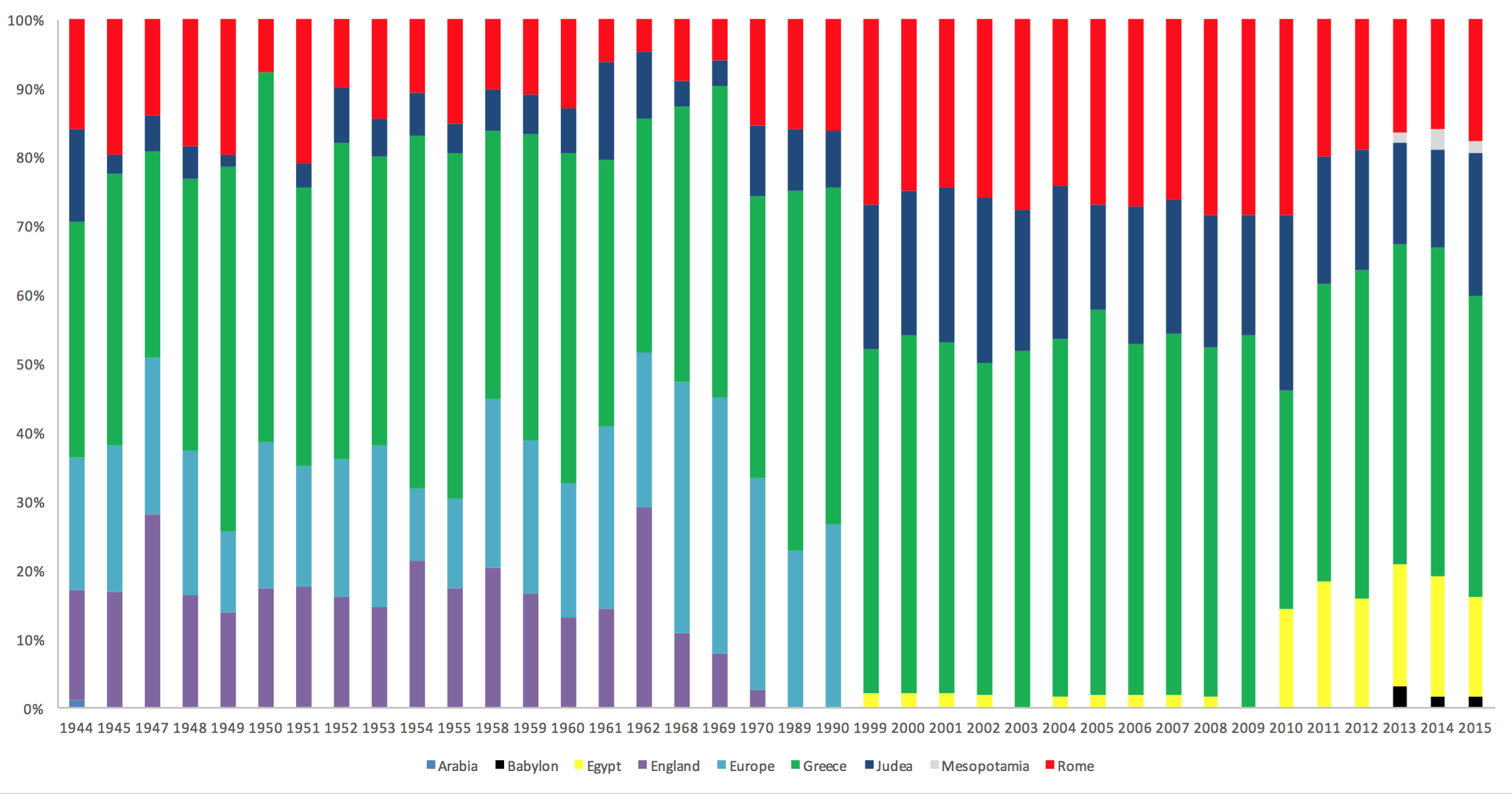

Reginald F. Arragon Professor of English and Humanities Robert S. Knapp (1974-present) provides a concise summary of changes up to the recent reintroduction of the Odyssey in a 2010 piece he wrote for Reed Magazine, “In 1979, the staff of the course proposed to take the further step of asking the Faculty to permit it to disband the common course, replacing it with a set of small, team-taught interdisciplinary seminars in subject areas of each team’s choosing. After extensive debate, the faculty rejected this proposal, instead reaffirming its commitment to a ‘unified Freshman Humanities course required of all freshmen, with a common intellectual experience, beginning with the Greek culture.’ Responding to that directive, the staff developed a new common syllabus, beginning with the Iliad and ending with Dante’s Inferno. That syllabus, first taught in 1982-83 [which probably motivated the introduction of Early Modern Europe (now Hum 220) in 1984], proved unwieldy and unfocused, so was replaced in 1993 with a syllabus beginning with Homer and ending with Augustine. Subsequent to the events of September 11, 2001, and at least partly in consequence of the way in which this event dramatically altered one’s sense of history, the Humanities 110 staff felt the need to examine the possibility of alternative syllabi for the course, but after lengthy deliberation, decided to keep the syllabus more or less as it had been… This syllabus, although divided into five areas of focus, provides for a unified look at the ancient Mediterranean world as a polycultural environment from the archaic period to the first century of the Common Era. We decided both to expand the geographical and cultural parameters of the course and to limit the chronological parameters in order to meet goals for the course which were expressed in various ways by faculty in the course, program reviewers, and students. The course continues to provide possibilities for a unified historical narrative that has now been extended into the second semester. It charts strategies of cultural assimilation and resistance, and does so with texts that are (1) aesthetically rich, (2) susceptible to multiple interpretations and disciplinary approaches, (3) thematically connected, (4) significant in the history of Western culture, and (5) eminently teachable. The syllabus also has significantly increased the amount of attention paid to material culture and urban environments. The syllabus, moreover, does not conclude with the ‘triumph’ of any particular culture or historical institution. Rather, it concludes with a Vanity Fair, a genre in which one continues to witness the contestation of values and identities” [4]. This refocusing on the ancient Mediterranean can be found in Figure 1 with the emergence of Egyptian texts as major primary sources [5].

The revised syllabus entered a three year trial period and was again revamped in 2013. Continuing the trend of broadening the cultural and geographic coverage of the course, Gilgamesh replaced Homer as the first reading, the Iliad replaced the Odyssey (though Figure 3a shows that the Iliad and the Odyssey had been trading places every now-and-then since 1943), and Babylonian texts were included.

On Narratives

In prior decades, there were weekly themes (since the Nineties they seem to come and go) and, after some time, broader themes. Reading these themes as a sentence can give us an interesting perspective on how various narratives were constructed; below are a few examples demonstrative of their respective decade:

1943: Introduction, Egypt and Babylonia; The Aegean and Oriental Background of Greece; Archaic Greece (Origins of the City-State); Rise of Democratic Athens; The Literary and Artistic Expression of Athens; War and the Ordeal of Athens; Fourth Century Individualism; Hellenistic Age; The Roman Republic, a Hellenistic Power; Social Conflict and Tyranny; Age of Augustus; Society of the Principate; Decline of Prosperity and of Public Spirit; Religion; Inheritance of the Middle Ages; Germans (and Arabs); Feudalism and Manorial Economy; The Medieval Church; Medieval Monarchy; Commerce and Town; The Renaissance; The Renaissance; The Reformation; Commercial Revolution; Absolutism and Parliamentarianism; Seventeenth Century Society and State; Science and Social Philosophy.

1953: Homeric Greece; The Greek City State; Greece and Persia; The School of Hellas; Crisis of the City State; Philosophy and the Decline of the Polis; Hellenistic Age; Hellenistic Thought; Rome: Republic to Monarchy; The Principate; Philosophy and Religion in the Early Empire; The Late Empire; The Manor; The Fief; The Church; The King; Dante; The Town; The End of the Middle Ages; Humanism; The Prince and the National State; The Reformation; Shakespeare; Capitalism, Mercantilism, and the Commercial Revolution; Seventeenth Century English Politics; The Rise of Modern Science; The Baroque; The Age of Louis XIV.

1964: Homeric Greece; Athens in the Age of the Persian Wars; The Periclean Age; Greek Philosophy; Rome: Republic to Principate; Roman Literature and Thought; Judeo-Christian Origins; Medieval Economy and Society; Church and State; Art and Scholasticism; Medieval Literature; The Renaissance and Renaissance Art; Italian Economics and Politics; Italian and Northern Humanism; Politics, Religion, and Society in the Sixteenth Century; Poetry and Drama in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries.

1967: The Heroic Ideal; The Development of the Polis; Classicism in Athenian Drama and Art; Critics of the Fifth Century Athenian Polis; Dante and the Medieval Tradition: Theology and Philosophy; Dante and the Medieval Tradition: Art and Literature; Dante and the Medieval Tradition: Politics and Political Theory; Dante and the Medieval Tradition: The Divine Comedy; Dante and the Medieval Tradition: The Problem; Renaissance Humanism: Humanist Thought; Renaissance Humanism: Humanist and Political Systems; Renaissance Humanism: Humanism, Politics and the Drama

1987: The Epic and Archaic Background; The Ionian Revolution; Imperial Athens; Reflection and Critique; The Creation of a Usable Past; Legitimating the Roman Imperium; Province and Metropolis: Christianizing the Roman Empire; Recreating Social Bonds and Political Associations; The Dantean Attempt at Synthesis.

Fall 1990: The Polis and Democracy; The Challenge of Imperialism to the Polis; Reflection and Critique/Polis and Individual.

2010: Epic and Foundational Stories; Didactic Literature; Material Culture; Lyric Poetry; Selves and Others; Democracy and Its Discontents; The Hellenistic World; The Roman Mediterranean; Models of Virtue and Vice in the Roman Empire.

Spring 2013: Philosophy in Fourth-Century Athens; Alexander and the Hellenistic World; The Growth of Rome in the Hellenistic World; Creating and Contesting Empire; Responding To Empire.

It is here, that we must unfortunately come to terms with what is missing from the archives. The Reed College Special Collection lacks syllabi from 1956-57, 1963-64, 1965-67, 1971-83, 1984-87, and 1992-1995. If you or someone you know happens to have any of these syllabi, please contact Special Collections. However, it is clear to see that there are stories that the syllabi tell (even when they don’t explicitly tell it) and that these stories change with academic and social trends.

Figure 1. Away from a Eurocentric syllabus toward a Mediterranean narrative of civilization. This time series omits years where data are incomplete or lacking from the archives altogether.

Figure 1. Away from a Eurocentric syllabus toward a Mediterranean narrative of civilization. This time series omits years where data are incomplete or lacking from the archives altogether.

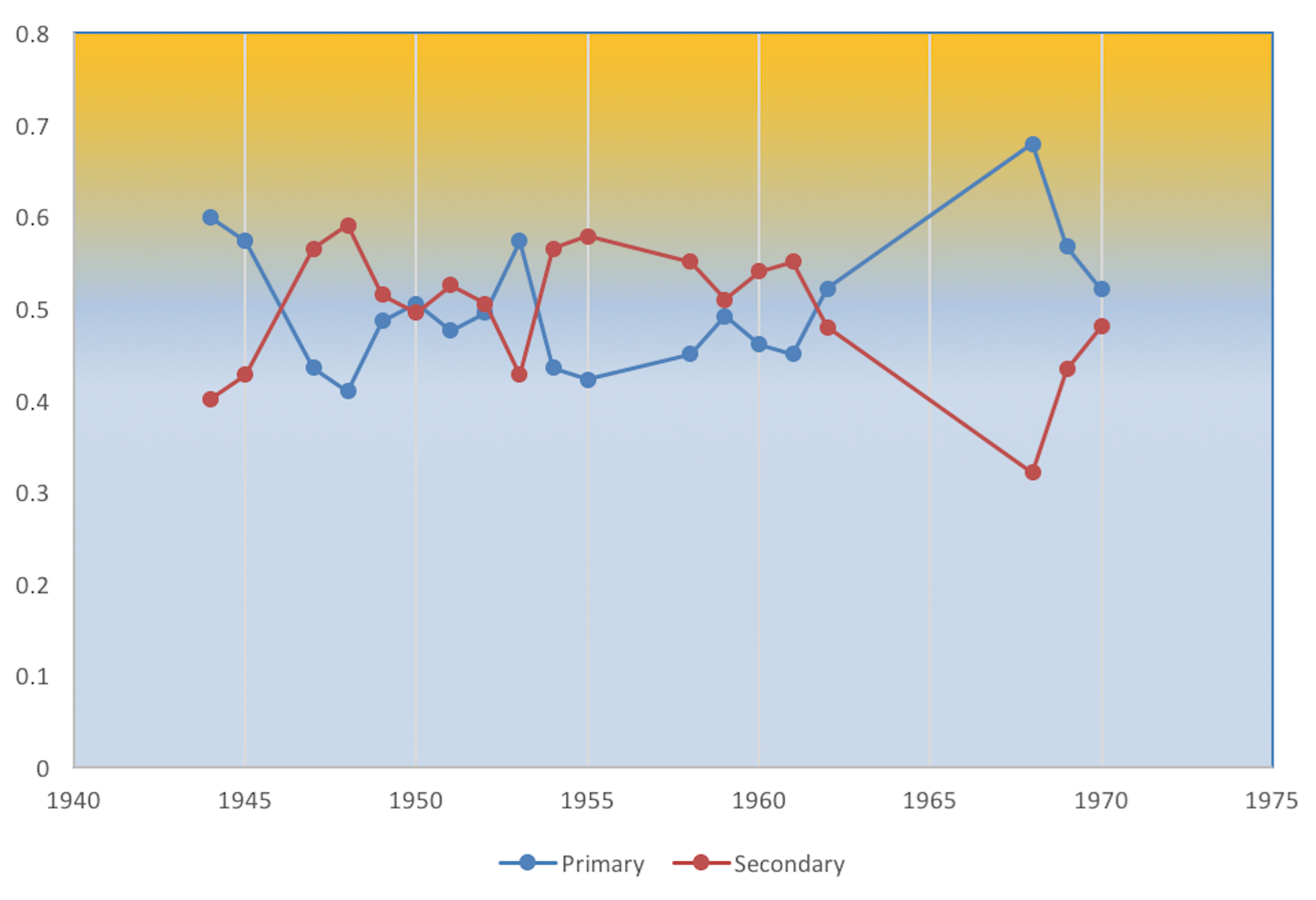

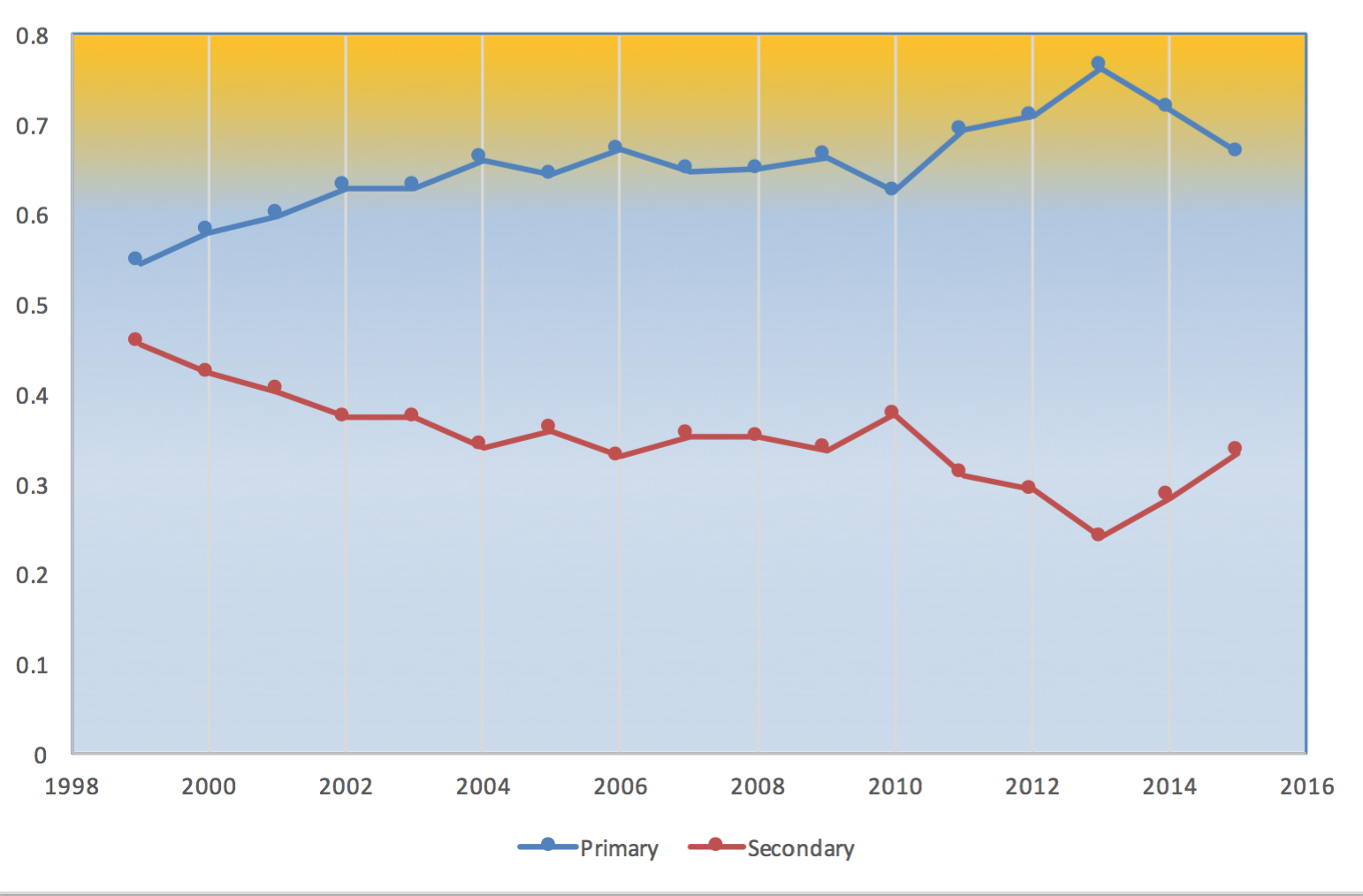

Secondary texts are crucial to the construction of these narratives and I wonder if students do not read enough of them (Compare, Figure 2a and 2b). The discursive space cleared for multiple interpretations and alternative narratives will undoubtably benefit from more critical voices, not in opposition but as supplement to the students’.

Figure 2a. We have more or less complete data for the 40s, 50s, 60s, 2000s and 2010s. Here, I present the percentage of primary and secondary readings of the total readings assigned for each year. It should be noted that Hum 11 was worth more semester credits before 1962 and could account for the reduction in secondary readings.

Figure 2a. We have more or less complete data for the 40s, 50s, 60s, 2000s and 2010s. Here, I present the percentage of primary and secondary readings of the total readings assigned for each year. It should be noted that Hum 11 was worth more semester credits before 1962 and could account for the reduction in secondary readings.

Hum 110 lectures also provide a smörgåsbord of amateur-professional and professional takes on the Classics by the faculty and it has been argued that this diversity of expertise (and even that of dilettantism) is the cornerstone which upholds the college’s claim that this is not a great books course. Robert H. and Blanche Day Ellis Professor of Political Science and Humanities Peter J. Steinberger’s account of the young analytic philosopher C.D.C. Reeves coming to Reed, discovering the Hum 110 canon through teaching, and becoming a world-renowned Classicist and translator of one of the finest translations of The Republic is certainly a compelling and inspiring story of the impact of Hum 110 on the life of the mind [6].

Figure 2b. A report from either the 90s or 2000s (I misplaced my notes here, will update this with a citation eventually) reviews the syllabus, “Many faculty… maintained that Hum 110 is not a’Great Books’ course. But from our perspective, it is a very close facsimile thereof, and one would be hard pressed to distinguish it from a class that teaches only the traditional literary canon. A principle problem lies in the absence of consistent and substantive presentation of historical context… In short, the expertise of historians needs to be brought to bear, not just token secondary readings which (so we understand) are rarely discussed in conferences…” I feel like they didn’t attend many lectures, many of which provide context for the reading, but perhaps they are right. Secondary texts certainly do represent a smaller proportion of the syllabus here as opposed to in the previous graph.

Figure 2b. A report from either the 90s or 2000s (I misplaced my notes here, will update this with a citation eventually) reviews the syllabus, “Many faculty… maintained that Hum 110 is not a’Great Books’ course. But from our perspective, it is a very close facsimile thereof, and one would be hard pressed to distinguish it from a class that teaches only the traditional literary canon. A principle problem lies in the absence of consistent and substantive presentation of historical context… In short, the expertise of historians needs to be brought to bear, not just token secondary readings which (so we understand) are rarely discussed in conferences…” I feel like they didn’t attend many lectures, many of which provide context for the reading, but perhaps they are right. Secondary texts certainly do represent a smaller proportion of the syllabus here as opposed to in the previous graph.

But is criticism enough? In his address on the 50th anniversary of the course, Professor Steinberger says, “If our course is a celebration of the Greek miracle, it’s a highly jaded, rigorously qualified, and deeply skeptical one. Our students know that Athenian democracy was, in an important, sense, constructed on the backs of slaves; that women led a profoundly privatized and marginalized existence in the polis; that the notion of the barbarian as an uncivilized and slavish creature is an absurdity; that the idea of a grand and widespread transition from the darkness and superstitions of the mythopoeic world to the openness and Enlightenment of Greek rationalism is a most dubious reconstruction of history; that Athenian democracy was, in an important sense, not very democratic, and Greek rationalism not very rational. In this sense, Hum 110 is virtually based on the notion that the canon is replete with frailties” [6]. However, there is now a growing student movement that says that criticism is not enough, that it cannot unchain the canon from the previous dominant (and oppressive) narratives, and the only real progressive movement is toward a study of non-Western texts. I do not wish to debate the merits of this argument here, for it is an ongoing debate among student and faculty of which I am neither. However, it is worth noting.

Great Books don’t move. Hum 110 has proven to be elastic. Unfortunately though I have tried, a good understanding of how the ideas, pedagogies, lectures, and texts interact throughout time requires that you look through the archives yourself (perhaps not that unfortunate), but I should be remiss to not present another example of things happening in the Hum 110 curriculum. When Bernal’s Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization was published in 1987, and its second volume in 1991, the syllabus proved to be dynamic and by the publication of the collection of essays Black Athena Revisited in 1996 (ed. Mary Lefkowitz), professors were teaching the controversy. Though there is substantial criticism of Bernal’s claims, academic interest in the role of Egypt in the Ancient Mediterranean was renewed and Professor of English & Humanities Pancho Savery’s lecture on Black Athena (among many other things) eventually lead to the adoption of Egyptian texts into the syllabus in 2010. David Eddings Professor of English and Humanities Nathalia King’s lectures on Gilgamesh likewise preceded its inclusion into the course in 2013.

Hum 110 acts as our Aγορά (gathering place), and though this particular exploration into textual changes and meta-narratives is interesting in-itself, it itself is not so important; the importance of exploration lies in livening our collective discourse and enriching our public sphere. Reed College may not be the pioneer, but it was certainly a pioneer of undergraduate conference-style curricula and Professor Arragon writes some words that still resonate today, “History too is a very ordinary way of thought, which links researchers, teachers, students, and laymen. We can with Carl Becker call ‘every man his own historian’, without supposing that each one’s history is equally good even for his own purposes. The raw materials, whether of the business office, the court room, the classroom or the archives, have to be arranged in some sort of pattern. College students, like research professors and men in the street, seek to interpret things that happen to them and that have happened to others. They ponder questions of evidence and of the relationship between happenings. They try to make sense out of their experiences and out of the materials of books, and in this process they draw on personal experience in the interpretation of historical events at least as often as they find light upon the meaning of what has happened to them in their study of books. Actions and words, potsherds and charters are baffling or indifferent to us except in some context. We have to reason out their connections to be able to judge their motive, their authenticity, their meaning for our lives or for the course of history. All of this thinking, and not merely that about potsherds and charters, is basically historical. The historical way of thought as an illustration of the common ground of teacher, student, and layman is significant beyond the field named History, for historical thinking more or less permeates the social sciences, literature, philology, and philosophy” [7]. I believe not only that the preeminence of history in the Hum 110 curriculum is the most essential aspect to the course’s uniqueness, but also that the continued study of the contextual nature of past historical narratives as well as our own will inspire spirited and fruitful discussion.

July 1, 2016

I hope you will glean something from perusing Figures 3a and b as well as the further reading provided after the references.

Figure 3a. Primary sources by author and title. Shaded columns illustrate an incomplete year with either the Spring or Fall semester missing.

Figure 3b. Secondary sources by author and title. Shaded columns illustrate an incomplete year with either the Spring or Fall semester missing.

References

[1] Reed College Quest, Vol 194, Issue 7.

[2] from Scholz’s first curriculum plan in Arragon, 1945 (see below).

[3] Quest, May 1961.

[4] Reed magazine, vol.89:1, March, 2010, pp.14-15.

[5] On the topic of diversity, it is of significance that in 1995 Chinese Humanities (Hum 230) was introduced to the Humanities offerings.

[6] A lecture given by Prof. Steinberger at the 50th anniversary of Hum 110.

[7] The Technique of Group Discussion by R.F. Arragon, Reed College Bulletin, vol.20:2, 1941.

Further Reading

3. A farewell to the Iliad by Robert Knapp. 2010.

4. Hum 110: the foundation of Reed’s academic community. By Romel Hernandez. 2002.

5. A 50th anniversary for Reed’s Humanities Program. By Harriet Watson. 1995.

6. Professor Reginal Arragon leading a Humanities Conference section, circa 1974.

7. The Development of the Reed Curriculum by R.F. Arragon, 1945.

8. The Technique of Group Discussion by R.F. Arragon, Reed College Bulletin, 1941.

9. A Curricular History of Reed College by Richard Jones, 1982.